Much of the information presented here was obtained from the book "Tales From the

Trees" published in 1981 by Ailene Hayes Schneider. Excerpts from an article by

Lisa Spencer in the book are also included based on interviews with Frank Wyepski

, a retired miner.

Anyone traveling through Central Illinois can't help notice the huge slag piles

that look like purple mountains. These mountains were created from the residue

of the mine and were called "Jumbo" by the local people. Minonk had two jumbos

that became identified as landmarks. Anyone returning to Minonk would know they

were home whenever they could site the jumbos. Unfortunately, the jumbo north of

Minonk was leveled and used as fill for the new Interstate built near Minonk in 1991.

The Minonk coalmines were opened in the middle 1860's. For many years it was the

main industry in Minonk employing 400 men at its peek. There were two mines.

The first mine was located at the north edge of the city and the newer one was

a half-mile north. The mine was 550 feet deep and mining was conducted almost

3 miles to the southwest. The soft coal was considered of high quality and was used

primarily for heating homes and producing steam for the industries throughout

Illinois. Normally, the mines were shut down for the summer due to the reduced demand for

coal. W. G. Sutton was the last owner of the mine when it shut down in 1950.

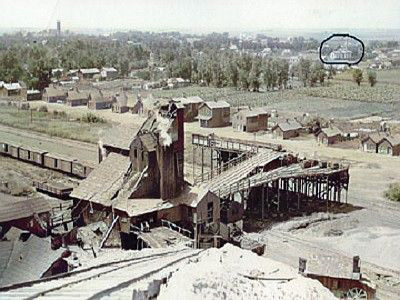

The photo to the left is looking southwest from the top of the jumbo over the

coal mine towards Minonk. The circled area shows St. Barbara's Church that

was built by the Polish back in 1890. The church is no longer standing.

The miners equipment consisted of a two-compartment lunch bucket, a carbide

lamp and a pick. The carbide lamp was attached to the miner's cap. The lamp produced light

by burning a gas created from the combination of water and carbide in the lamp. After

lighting the wick the miner could control the amount of light by adjusting the flow

of water. The miners 's pick was sharpened each night by the blacksmith. Each day

the miners would spend 20 minutes being lowered into the mine.

Each then would go to their individual rooms where they would complete their "gobbing", a process

in which rocks are layered on top of each other to form a support wall where

they would be digging. Coal would be loaded into a cart and then hauled by a

mule to an electric train, which transported it to a hoist, which carried it to

the surface. Water continuously seeped into the mine and had to be removed by pumps daily from 2:00 am to 7:00 am.

Working conditions in the mines were harsh as it is with all mines. But all of

the miners took pride in their work. Life was not easy for the earlier miners

as many of them lived in makeshift shacks built by the mine owners on the road

leading to the mine. Many of the miners would go to the local saloons after work and

fill their large tin buckets with beer before returning home.

1894 Strike

While there were periodic strikes for better wages and working conditions none

resulted in any violence except for the strike in May 1894. Below is an excerpt

from the newspapers describing the strike.

Minonk, Ill., May 28. - Last Saturday 200 Poles, Belgians and Huns from the

coal shafts in this town squatted on the embankments at the junction of the

Illinois Central and Santa Fe tracks. The crossing is over 100 yards from

the station. These 200 sallow-faced and savaged-eyed strikers were stationed

at the junction for the purpose of preventing cars with coal from going to

Chicago. They piled ties on the tracks and thrust coupling pins into the

frogs of the switches. These obstructions were removed when the passenger

trains or trains bearing anything but coal steamed slowly up to the crossing, but

they were quickly and securely replaced the instant the railroad company

attempted to move the coal-laden cars standing on the siding.

To quell the strike the Illinois Militia was called. Three strikers were arrested

and fined. The trains began to move again. However, the angry miners and

their families appealed to Mayor Simpson for relief stating that their families

were starving. They had not eaten for 3 days and had no money for food.

At a meeting the deputy sheriffs brought in to keep the peace voted to give part

of their pay to the needy miners and their families.

Company Store

The miners were also victims of the company store in which the miners would

exchange script for the over-priced goods. Below is an excerpt from the local

newspaper about those conditions.

They are reported as living for days on a crust of bread and families have

gone three days without food. The causes of this, the strikers say, lie in the

miserable working conditions of employment. Lured here by promises of steady

work and good pay, they have not averaged in actual value received for the

hardest kinds of work, twelve and fourteen hours a day, more than 90 cents.

The Miner T. Ames estate, which owns the mines here, insists upon the men trading

out most of their pay in the estate's truck store, discharging those who refuse

to do this. Several of the leading merchants here said today that the prices

at this store were much higher than at other places in town, offering in proof

that the miners never use cash at the truck store, going elsewhere for less

expensive goods. One man said that 40 per cent was the average profit the

Ames estate made on the goods.

With the increased unionization of the mineworkers, the mine's company store ceased

to exist sometime in the earlier 1900's.

World's First Street Lights

Local residents like to mention that Oak Street in Minonk was the first

electrically lighted street in the world. Evidence to support this belief

appears in an article written by Seymour Berkson for a Chicago newspaper.

Knowlton L. Ames, prominent Chicagoan and head of the Booth Fisheries

Company was born in Minonk. It was through the efforts of his father,

the late Minor T. Ames, that Minonk was the second town in the United

States to have municipal electric lighting.

A friend of his working at the time for Thomas A. Edison in his electrical

laboratories. One day he came to visit Ames. After he saw the mine he

offered to install electric lights in the shaft more or less as an experiment.

That was in 1882. It worked so well, Ames gathered a group of subscribers

and had electric lights installed throughout the town.

Local legend has it that a transformer was installed at the original mine and

light bulbs were strung south from the mine along Oak Street to Seventh, then

west to the Mine Store at the corner of Chestnut and Seventh streets.

Clay Pit

At the south west of the original mine was a deep pond called the "Clay Pit".

The pond was originally dug as a reservoir to provide water for the clay and tile

works south of the coal mine. This pond was used

by the local children for swimming for many years. In the 1920's a young man

drowned in the clay pit. Automobiles were brought to the pond and their

headlights were pointed to the area were the divers were searching for the

body. Old timers who remember this event said that it was a quite eerie

and gloomy scene. Nevertheless, people continued to use the pond for swimming.

Years ago circuses and carnivals came to Minonk and they would set up their

tents in this area south of the Jumbo. There are stories of a circus elephant

that died at one of these events and was buried in the clay pit.

The clay pit was filled in sometime in the 1970's and is now the site of a

mobile home park.

MINE MULES

A rememberance by Barth Weistart

The mine closed last Saturday noon

The mules were brought to the top

that afternoon and are now enjoying

a well-earned vacation in the sun-shine

and fresh air.

The Minonk News April 4, 1912

I recall walking with my father to see the mules that had been brought out of the mine for the summer. They were pastured in the Sutton field at the North end of Oak Street and just south of the Jumbo. The field had been the site of the No.1 Mine and the Chicago and Minonk Tile and Brick Company in the 1800's. In the 1940's, a three sided barn was located between the bricked in air shaft for the No.2 Mine (orginally this was the No.1 mine mainshaft) and the clay pit. The barn was used to house the mules during their summer break. The mine usually closed down for a month or two during the summer because of the low demand for coal.

The mules were taken down in

the mine on Tuesday and work resumed yesterday morning. There is

not much demand for coal now and

it is expected that the miners will

only work a few days each week for

a while.

The Minonk News May 9, 1912

The mules were given unique names. There was Blackie a large Jack who let very few approach him. Dad was one who could approach and pat Blackie. This came from years of working together in the mine. Two other mules were Gee and Haw. In the days of working animals, gee and haw were commands used to tell animals to go to the right or left. In the long straight passages of the mine, commands to go right or left were probably little used.

In their stalls and field, the mules could be seen lifting there heads and smelling the air. Dad said they were fascinated with the smells of the world- the flowers, the hay, the rain, the trees. Their life was dark passages 500 feet underground filled with smells of gasses and coal dust. Their month or two above ground was a gentler but foreign environment.

After three years, the mules were totally blind. Being brought up into the light was a shock to their systems and detrimental to their eye sight. Some mules wore blackout blinders to save what little sight they had left. Miners in the Cherry Mine Disaster, who were sealed in a totally dark passage for 21 days had to wear sacks over their heads when brought out of the mine because of the intensity of the light. Eventhen, several complained of headaches for days afterwords.

Mules would resist going back into the mine although most accepted their fate and returned to the enviroment with which they were most familiar. Until the latter part of the 1800's, mules were the power that ran the mines. They were used to pull coal cars from the working face of the mines to the shaft to be hauled to the surface. Mules on the surface would pull up the cage with the coal cars. Slag (rock,clay and other matter dug with the coal) was also brought to the surface and dumped to form The Jumbo. The first Jumbo, which is now part of a freeway overpass, was a pristine example of technological change. The north portion of the Jumbo had a gradual rise attaining greater distance than height. This portion of the Jumbo was formed by the load of slag pulled to the top by mules. With the advent of machines with wenches, mules weren't needed to dump the slag. Greater heights in forming the Jumbo were attained by using machines. The south portion of the Jumbo had a much steeper incline contrasting the use of machines over mules. Few if any Jumbos in the Minonk area, so dramatically reflect our countries change from muscle power to industrialization.

John M. Boland who is employed in

the coal shaft as driver, was kicked in

the face by a mule Thursday evening

of last week. His nose was broken,

and his face brused. His injuries were

dressed by Dr. Fred Wilcox. The

mule got away after kicking John, and

it took the boys a good while to round

him up.

The Minonk News January 25, 1895

Working with the mules could be hazardous both for the driver and the mules. Mine tunnels followed the coal veins so they were not always flat. A mule pulling a coal car up a slope was not a problem. Going down a slope was! The car had to be braked or it would roll into the mule. Early brakes were pieces of wood pressed against the metal wheels. The brakes were often insuficient, broke or worn out. The driver had to sit on the front edge of the car and press his foot against the steel rail to slow the car down. One slip and a foot could be mangled. This procedure was wearing on shoe leather. Many drivers would use old car tires to retred their shoes. The car tire soles were an improvement and more durable.

K.L. Ames recently bought some

new mules to work in the mines, and

last Thursday while assisting the

blacksmith put shoes on one of them,

Mike Shea was kicked in the face. His

upper jaw was smashed in, and it will

likely cause Mike to be disfigured for

life. Mike has the sympathy of large

circle of friends for his untimely

trouble.

The Minonk News October 14, 1897

Pictures of mules in a mine are rare. Minonktalk has just such a picture in its collection. Look under History- Old Photos-Coalmine Mule.

You won't see many like it. Also, at this same location, "Minonk Jumbo" will give a visual of the slag pile made by mule strength and the slag pile (to the right) made by machine power.